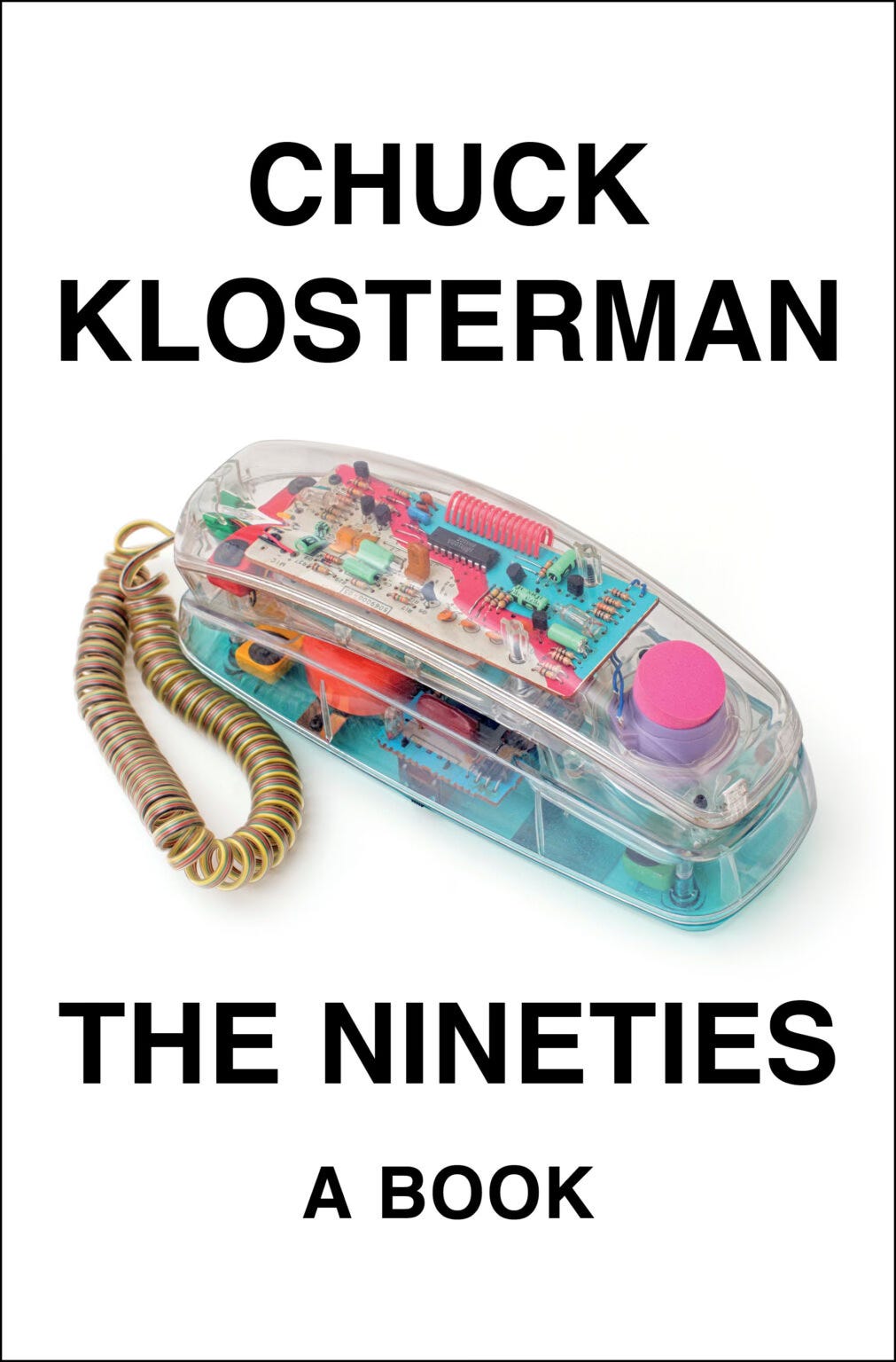

Did You Ever Have a Clear Phone?

Subscription giveaways and the incomprehensibility of the past

First, some thoughts about tote bags…

As an expression of personality and taste, tote bags have ascended to the level of t-shirts. On a city bus, in the park on a sunny day, or in line at the grocery store, you’ll see canvas carryalls that tell you what a person reads, where they shop, what they listen to, and which charities they support.

The longtime public radio reporter in me smiles whenever I see a tote. For years, NPR and its member stations had the lock on giveaway bags. They turned a tool for hauling ice into a sign of urbanity. In the last decade, The New Yorker seized the canvas crown, flooding the streets of upscale neighborhoods with totes that came free with a discounted trial subscription

Tote bags aren’t costly to make, they don’t require variations in sizing like t-shirts, and they’re imminently useful. For NPR in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, the canvas tote was an easy enticement for listeners who were likely ahead of the curve on bringing their own bags to the grocery store. For magazines looking to boost subscriber numbers (and ad rates) in the 2010s, it made sense to offer an accessory to farmer’s markets, boutiques, and other places where rosé, baguettes, and artisan cheese can be found.

Now the tote bag is the default way businesses and nonprofits say “thank you.” The hook on my kitchen door is weighed down with reusable bags. There’s the luxe, multipocket numbers that come each year from Monocle, the wry Joan Didion tote from Literary Hub, at least one each for The New Yorker, New York, The New York Review of Books, The London Review of Books, The Paris Review, and bags for libraries, bookstores, and museums that we’ve lived near. On the tram around Basel, I see bags for Parisian bookseller Shakespeare and Company, for local plant stores, and, surprisingly, for online bedding retailer Brooklinen (I say “surprisingly” because international shipping is expensive and bedding is different sizes in Europe.)

Each bag advertises a business. Each bag advertises a personality.

Now, about phones…

The criteria for a good giveaway—cheap to make, generally useful, easily branded, one-size-fits-all—don’t just apply to tote bags. Gym bags and fanny packs were once popular. Time magazine gave away digital watches, radios, and desk clocks. I’ve seen binoculars, multitools, pencils, and notebooks with now-defunct magazine titles on them.

But the most iconic giveaway from the pre-tote-bag era is also one of the strangest: the Sports Illustrated football phone.

The football phone is exactly what it sounds like—a phone shaped like a football. It’s origins aren’t so simple.

Sports Illustrated first rolled out the football phone in 1987. At the time, the concept of a novelty phone was still pretty new. For many Americans, the concept of owning a phone at all was new. Until the government broke up the Bell Telephone monopoly in 1982, people in most states leased their phones from the phone company. When a new type of phone came along, customers had to get it from the phone company and pay a monthly fee for it. In some states, customers could buy a phone outright, but they had to buy it from Bell. Here’s an article from 1975 in the Philadelphia Daily News taking Bell to task for obscuring the option to buy a princess phone and instead charging customers a monthly fee for the handset. In this ad from 1960, a store offers to arrange for Bell to put a new phone in the house of anyone who buys a new camera. If the customer also buys a projector, the store will pay rent on the phone for a year.

Novelty phones weren’t entirely unheard of in the early ‘80s. The Federal Communications Commission cleared the way for independent phone manufacturers in the late ‘70s, and stores like Radio Shack sold phones shaped like Mickey Mouse, phones made of clear plastic, and phones built into alarm clocks. “People want to have the phone as part of the decor,” a Southern Bell spokesperson told The Charlotte Observer in 1980. But this was still a niche market. Novelty phones cost hundreds of dollars, and only one out of every twenty-nine phone customers bothered with them. The Bell breakup blew the novelty phone market wide open.

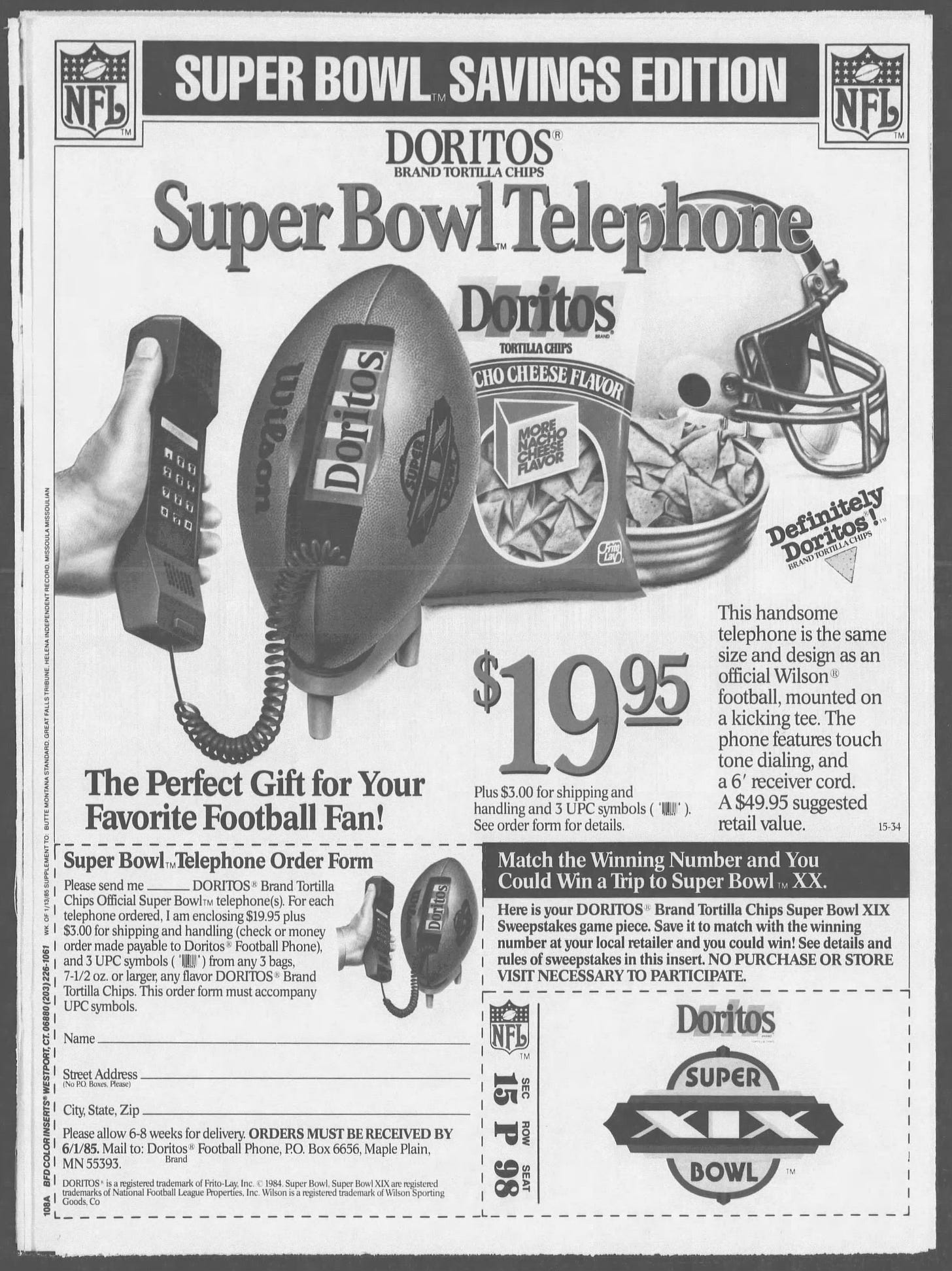

Sports Illustrated wasn’t the first to make a football-shaped phone. The Charlotte Observer article mentions one. And Doritos gave one away in 1985. But Sports Illustrated was the first to run ads for the product endlessly on cable. This gave the phone exposure and indelibly linked the phone to the magazine.

In the ads for the football phone and the sneaker-shaped phone that came later, Sports Illustrated makes it clear that the devices work like regular phones—you press buttons and make calls. Customers are delighted at this and shocked at the novelty of the phone. It’s easy to look at these ads and think of the past as a simpler time, but at the time, the phone as an expression of taste or personality was a new concept. For most adults, a phone was a thing a technician put in your house and a big company charged you to have. Phones looked like phones. Now they looked like balls and shoes.

SI also capitalized on another growing home technology—the VHS tape—and offered subscribers videos of sports highlights and goofs (we never had a football phone, but I watched our copy of Dazzling Dunks and Basketball Bloopers so many times I could recite it from memory in first grade). But it was the football phone that became part of pop culture. Rolling Stone credits it with moving millions of subscriptions in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. (Speaking of Rolling Stone, for years I carried around a CD wallet that came with a subscription to the magazine.) The phone was everywhere.

If you grew up with a landline phone, chances are you have a strong memory of it—the way it looked, the way it sounded, the way the receiver felt in your hand. These were devices we spent hours on. They were central and vital fixtures in the home. This made the novelty phone all the more powerful. It was a statement to have fun with something so important to the functions of daily life, to have your connection to the outside world look like a cartoon character or athletic equipment.

The last gasp of the novelty phone in pop culture was in the 2007 movie Juno. The title character talks on a phone shaped like a hamburger. Fox Searchlight even made branded phones to cash in on the movie’s (and the prop’s) popularity.

2007 was also the beginning of the end of the landline. The iPhone launched that summer. The phone remained the center of our lives, but the wacky shapes and endless variety vanished, as every phone—whether it was made by Apple or not—began to look the same, like a glass rectangle. The customization is in the software you put on the phone, not the shape of the device. There’s nothing to project, except maybe in your choice of a case (or the tote bag you carry your phone in).

Good luck using a novelty phone if you have one. Phone companies are ending their traditional land line service in favor of Internet-based service. There are some vocal holdouts who point out that land line service is still more reliable than cellular and web-based calling. But we’ve reached a point where keeping a home phone is considered quaint, or maybe quirky. The most novel phone you can have anymore is a landline.

I def had a clear phone as a teen in the 90s. My family phone in the kitchen was also shaped like an old-fashioned firebox--to use it, you had to open the door. Pretty awesome, actually. https://www.ebay.com/itm/404996296771