To subscribe to the audio edition of the newsletter, find it in Apple Podcasts, or add the feed to your podcast app of choice.

For most of the summer, Kate Bush's “Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God)” has been in the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100. It peaked at number three. The song is 37-years-old, and its popularity is driven by its appearance in the show Stranger Things.

This is unusual, but it’s not unprecedented.

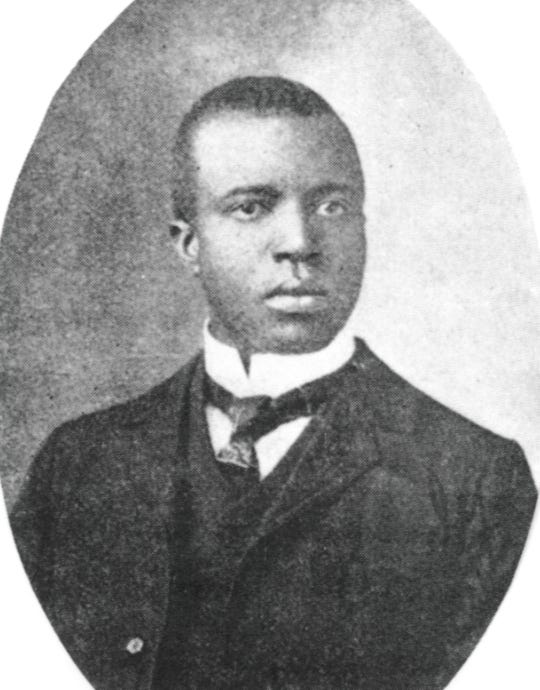

In the spring and summer of 1974, Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer” was in the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100. It peaked at number three. The song was 72-years-old, and its popularity was driven by its appearance in the movie The Sting.

To be precise, Joplin was not on the charts in 1974 as a performer. The version of “The Entertainer” that charted was Marvin Hamlisch’s recording from the movie soundtrack. But don’t dismiss it as a cover, or its chart position as an event closer to The Chicks charting with a cover of “Landslide.”1 “The Entertainer” predates recorded music. The only way Joplin could chart is if a long-lost wax cylinder or piano roll of him playing his song made it to wide release (or if Billboard decided to track sheet music sales). Hamlisch’s recording doesn’t add any modern sounds, sensibilities, or pop star power to the song, like a cover from a well-known pop act would. The main variation is in orchestration; Hamlisch uses horns and clarinet to interpret the familiar tune. “The Entertainer” also predates modern pop music as a genre. The sonic distance between a ragtime piano composition and the hits of 1974 is far greater than any popular cover is from any original. (I’ve written a piece looking at the oldest songs that have landed on the charts via covers.)

To further complicate the comparison to “Running Up That Hill,” “The Entertainer” reached the charts under 1974 rules—when rankings were determined by record sales and radio play.2 Some two million people paid money for the 45 RPM single of Hamlisch’s recording. Millions more heard it on pop radio stations. Today’s charts are determined by streaming, in addition to sales. It’s not easier for an artist to get on the charts now, but it is easier and cheaper for fans to help an artist get on the charts.3

I don't mean to downplay the brilliance of “The Entertainer” by questioning its popularity in the ‘70s. Joplin was a genius. Without his contributions to music, a lot of what was on the radio in 1974 might not exist. And there’s nothing unusual about listening to older compositions or recordings—“The Entertainer” wasn’t out of date. But in a pop music context dominated by acts like Stevie Wonder, Wings, Kool and the Gang, and Abba4, a straightforward ragtime piano tune seems a little out of place. When lawmakers were debating impeaching Richard Nixon, pop DJs in America were spinning ragtime.

How did this happen?

Well, for one, The Sting was huge. It opened on Christmas in 1973 and made the kind of money we only see superhero movies make now. It grossed $156 million, the equivalent of over a billion dollars today. In April 1974, it won seven Academy Awards, including Best Score for Hamlisch. The next year, the song won Hamlisch a Grammy, setting him on the path to becoming one of the 17 people to win an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony, and one of only two to win a Pulitzer in addition to the EGOT.5

Pretty much everyone who went to the movies saw The Sting. And pretty much everyone who saw it wanted to hear the music from the movie at home. While “The Entertainer” was climbing the singles chart, the soundtrack to The Sting was the number one album in the country. Not only did people want to hear “The Entertainer,” they wanted to hear an entire LP's worth of Hamlisch's Scott Joplin recordings.

The success of The Sting explains how Hamlisch's recording of Joplin became so popular, but the movie can hardly be credited with making Joplin popular. If anything, the movie score was drafting on Joplin's success in the ‘70s.

Ragtime had been growing in popularity since 1969. That year, Eubie Blake, one of the original ragtime composers, born 19 years after Joplin, put out a career retrospective record. The record made the 86-year-old a star. He toured and appeared on TV for the next 14 years.

In 1970, the record label Nonesuch put out the first of three albums of Juilliard graduate Joshua Rifkin playing Joplin compositions on piano. That same year, musician and historian Vera Brodsky Lawrence edited a two-volume set of Joplin’s sheet music, which the New York Public Library published. It was the first time anyone had published the complete works of a Black composer. Two years later, the Atlanta Symphony and the Morehouse Glee Club staged the first-ever production of Joplin's opera Treemonisha.

When The Sting left theaters, the United States was five years into a ragtime craze. The music, movie, and publishing industries were profiting from ragtime remembrances and reissues. Academics studied it. Audiences ate it up. In 1974, The New York Times made reference to “the ragtime tidal wave currently deluging America.”

So what happened to the wave? Why isn’t it as well-documented or as resonant in popular culture as the ‘50s revival that happened at the same time? Sha Na Na played Woodstock; American Graffiti was up against The Sting for Best Picture; Grease, Happy Days, and Don McLean's “American Pie” persist in popular culture. But search the archives for articles about ragtime from the 1970s and you'll get more results about the E.L. Doctorow novel than the music. Beyond the Times article I referenced in the last paragraph, there's very little I can find from the ‘70s that explains or documents the ragtime revival—outside of mentions in academic papers.

The closest thing to the ‘70s ragtime revival in modern memory is the swing craze of the ‘90s. Once again, in a time of rapid musical innovation, sounds from seventy years earlier exploded on the charts and airwaves. Compared to its precursor, the swing revival is well-documented. It's one of the things only ‘90s kids remember—preserved on the fringes of confused nostalgia for third-wave ska, underneath the career of Vince Vaughn, and algorithmically boosted whenever YouTube shows someone an old Gap ad.

In all this media, I think I found the answer to why the ragtime revival isn't as well remembered today. It’s not that it didn't lead to new memorable media—The Sting, Eubie Blake’s later career, and the Joplin re-recordings are proof enough. I think the ragtime revival faded because of the media it was based on—sheet music and academic citations.

Compared to the turn-of-the-century, the ‘50s and the swing era left behind heaps of cultural artifacts that were still in circulation for the revival. There were movies and records and (with the ‘50s) TV shows. They could be re-run and re-interpeted. You could put on a Benny Goodman album or you could watch a Brian Setzer music video. You could buy a Buddy Holly retrospective or watch Grease. If you wanted to participate in the ragtime revival, you had to see an active band do their interpretation, buy a new record, or see a new movie. The source of media was people who could read music or had access to archives of journals of musicology. They were the narrow bridge from the original to the new. There were no reruns to riff on, and no mass memory to mimic. Sure, someone could look up an old photo print and try to dress like that, but the past that lives on paper feels much less alive than an era stamped on wax, burned onto celluloid, or beamed into our homes. That past is preserved in motion.

When we capture something in motion, it’s never as sharp as it was at first. It’s blurred and distorted. Literally, it’s mediated. One hallmark of the ‘70s ragtime recordings is the fact that they were done at the slower tempo that would have been more common to the original, and less common to recent recitals. Hamlisch used period-appropriate instrumentation on his records. There was mass appreciation of ragtime, but not a mass understanding that was deep enough for camp interpretations to emerge. The ‘70s version of the ‘50s and the ‘90s version of the ‘20s were campy in a way the ragtime revival wasn’t. Grease is a caricature of the '50s. The swing revival took on an ahistorical tinge of ‘50s greaser attitude in the ‘90s. There’s an exaggeration and a selective filtering that happens with a populist revival, and the works that make it through this filter set the revival apart from the original and gives it its own stamp in history. This wasn't the case with ragtime. It was straightforward, accurate, and destined to be short-lived.

This was the song the band had on the Hot 100 when singer Natalie Maines criticized George W. Bush. It might’ve charted higher if not for the political backlash.

Well, by purported sales and radio play. There are plenty of stories about unscrupulous record store owners misreporting sales to move unpopular product in the years before sales were measured by barcode scans. But these stories tend to focus on how such inaccuracies kept mainstream rock on the charts.

When I first saw “The Entertainer” on an old Billboard chart, I assumed it was the Billy Joel song of the same name, which also charted in 1974. I’ll also admit that, until recently, I thought Joel’s “The Entertainer” was, in fact, his recording of Scott Joplin’s song (he was the Piano Man, after all). It wasn’t until I started working on this post that I realized Joel’s song was different, and was also a hit.

In Billboard's year-end singles chart, “The Entertainer” finished one spot above “Waterloo,” which won the Eurovision Song Contest that year.

Besides his win for The Sting, Hamlisch won two other Oscars that night for his work on another Robert Redford movie, The Way We Were.

Share this post