If you want to listen to this essay, perhaps with some music I made underneath, then you can become a paid subscriber. You’ll get a weekly audio edition as a podcast or email. You can also support the newsletter just to be nice. You don’t have to listen.

Everywhere I look, I imagine building a shelf.

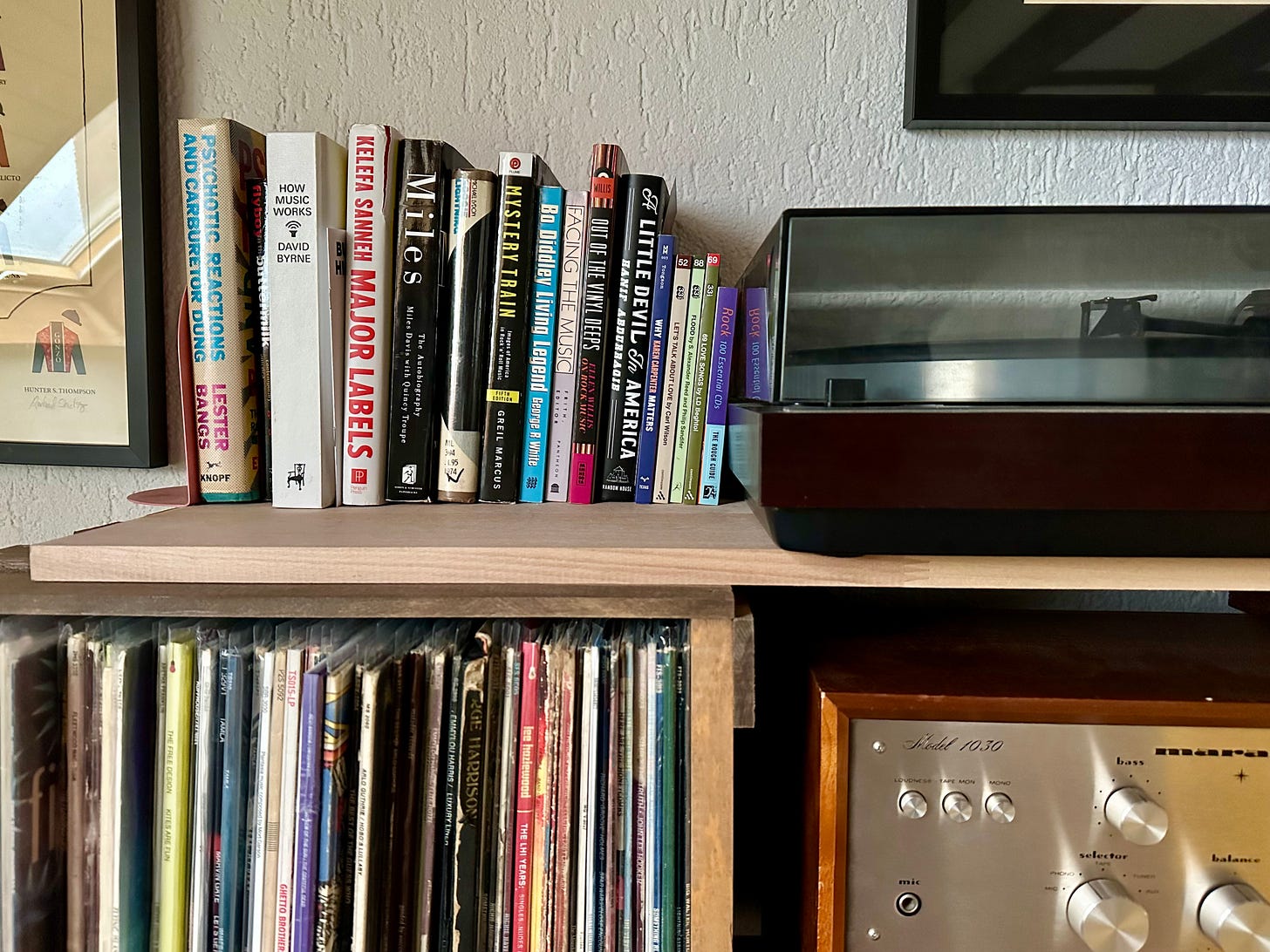

As I write this, I’m staring at an odd corner in our apartment where two walls meet and the ceiling slopes slightly and I’m thinking how, with a couple planks of wood and some nails, it could be home to a few dozen books. Behind me is an assemblage of beams and old crates I concocted to hold all of our records and the stereo that plays them, plus a selection of books and framed photos that should go on another shelf, as soon as I find (or make) one.

I’ve loved shelves ever since I learned how to read, and that love only grew as I discovered music. It’s a particularly wonderful feature of books and albums that the best way of storing them is also the best way of displaying them, and there’s not a strong distinction between a display for your own perusal and a display that tells anyone who visits your home just about everything they need to know about your taste. A shelf is home to hundreds of little pieces of furniture you’ve spent hours of your life with. There’s a joy that comes from finishing a book or listening to a new record and then adding it to the collection.

In the introduction to the essay collection Loitering, Charles D’Ambrosio writes about a “somewhat wobbly arrangement of brick-and-board shelves” in his childhood room.

In private, I thought of those shelves with enormous pride, as something I was building, book by book, and brick by brick, and I often looked at them, vaguely satisfied, like a worker inspecting the progress of a job. I wanted the shelves to rise up and reach the ceiling, and for that to happen, all I had to do, I realized, was read.

I read that line, then I read the whole book. A week later, we moved apartments and needed new shelves. I went to the home improvement store and bought sixty bricks and twenty-four feet of lumber to build my own shelf that wasn’t quite so wobbly. The plan was to eventually get some more professional shelves, but we kept the bricks and boards for eight years. They fit. They spoke almost as loud as their contents, implying that we were so overloaded with reading material we couldn’t bother to go to IKEA or put hammer to nail. I suppose this is true.

The records have always had their own shelves, but when I was designing their new home, I made sure to build in space to keep all our music books nearby. I had a vision of organizing everything thematically—books about music near the music, books about film near the TV, cookbooks in the kitchen, books about books near the books. Looking for a book that explains what the mixolydian mode is? It’s somewhere near the mandolin.

When I come back from a trip or a long day, the full shelves tell me I’m home. But for a long time, my most important shelves traveled with me. From the moment I started driving until the day I sold my last car, I never got behind the wheel without at least one CD wallet on hand. When I shared the family car, I carried my CD wallets with me on my turn to drive, considering it impossible to go even to the local bowling alley without at least three days worth of listening. These were my desert island discs, though in truth they were all the discs I had. They were my comfort when the whole world felt like a desert island.

When our home computer gave us the ability to burn CDs, my wallets held copies of all the discs I had. My CDs were worth almost all the wages of my summer jobs, and taking them with me places felt like carrying my life savings around. After our technological upgrade, whenever I got a new CD, I ripped it to our computer’s hard drive, burned a copy for the wallet, then put the original back in its case and set it on a dedicated shelf.

(Let’s take a moment here to remember CD shelves. Sometimes they were made of wire, sometimes of molded plastic, or sometimes of wood spaced just the five inches needed to house a jewel case. Whatever the material, and whether they stored cases horizontally or vertically, the shelves were useless to hold anything else. These shelves embody the dominance of the CD era and the hubris of the industry. Labels were selling millions upon millions of CDs and American homes needed specially sized shelves to hold them. No other shelf would do, and no other shelf would ever be necessary. Seeing a CD shelf now is like seeing Ozymandias’s legs in the desert. Look on my tracks, ye mighty.)

Unlike a CD shelf, the wallet was practical. Unlike any shelf, it was portable. But like a shelf, the CD wallet was a prized possession—a concentrated case containing the art I held most dear, the culmination of my ever-evolving cultural education, and an instant conversation starter. Stuck in traffic or in-between rest stops on a long drive, nothing could get us talking like a passenger’s perusal of a CD wallet in search of the next album. The true beauty of the CD wallet was in the main way it wasn’t like a shelf: its contents were uncertain until it was opened. On the outside, it was clearly a bunch of CDs, inside it was a collection unique to the owner. There’s something intimate about going through someone’s CD wallet. There’s the name, wallet, a place where we hold important documents and private information. There’s the way we open it, unlatching or unzipping, like clothing. And there’s the way we flip through, like the pages of a photo album, a surprise with each turn.

CD wallets were the first items to pop out of backpacks on field trips and the first thing anyone checked for if their bookbag went missing and wound up in lost and found. In summer, we moved them from our backseats to our trunks. In winter, we clumsily flipped pages with our gloves on while our cars got warm. We preferred them over the sun-visor disc holders, which never seemed like they offered enough protection for such valuable pieces of culture.

I got a CD wallet for Christmas every year until the year I got the gift that put an end to them: an iPod. Steve Jobs promised 10,000 songs in your pocket, and with a tape adapter the contents of my pocket could fill the car. I loved the convenience, but sharing was harder. The intimacy and joy of flipping through a wallet and determining what each CD was gave way to reading a list of uniform text. We scrolled too fast. We skipped. We overlooked, ignored, got overwhelmed, and in the end we just chose to shuffle.

Now there’s no need for even a portable hard drive. Everything streams, even the music we don’t own. The endless choice and instant access is convenient, but something is still missing. Our taste isn’t revealed through browsing but instead it’s shaped by a machine with infinite knowledge of recorded music and inside information on our habits—past listens, browsing history, Amazon purchases. Our playlists are as personal as our credit scores and just as fun to share. Streaming music and ebook subscriptions give us all the access of living in a library but none of the fun of having someone come over.1

Bookshelves, too, are changing. More than a decade ago, IKEA modified its Billy shelves to accommodate tchotchkes in addition to books. Occasionally a trend piece about “shelfies” pops up, but there’s something frustrating about a cropped, filtered photo of a shelf. A viewer can’t reach out and browse. They can’t look on a high or low shelf and see the titles you’re hiding. Curating a shelf for a photo shoot is nice, but it’s not the same as cultivating a shelf through life.

We don’t have to share something to like it, and we don’t have to call attention to every piece of culture we consume. A visible collection is a way of passively saying something about who we are—a way of revealing our personality and sparking a conversation. It’s also appealing. This isn’t an epitaph for the crowded shelf. Indeed, there is a sign of life. A study earlier this year estimated that half of the people who buy vinyl don’t even own a turntable. These are display copies to accompany their streaming; something physical for a digital world.

As we were packing for our latest move, Linda pulled a CD wallet out of a closet. Inside were all the mix CDs I’d given her when we first started dating. A few months later, when I was back at my parents’ house, I found my old CD wallets, with all the mixes Linda had given me. Whenever I borrowed their car for a day trip, I brought one of the wallets with me. It was a trip through time just flipping the pages.

In this age of infinite streaming, what has become of the CD wallet? As recently as 2022, Rolling Stone was testing, reviewing, and recommending CD wallets. (The first subheading in this review is “How Do CD Wallets Work?” which strikes me as either a sign of changing times or an SEO play that I don’t fully understand.) Case Logic, the company that made so many CD wallets, is still in business, still making wallets, along with backpacks, laptop sleeves, and all other neoprene nests for your gizmos. Confusingly, the company website lists “Dance” as one of its categories, though it just seems to list products one might wear on the way to dancing, or to hold devices that play music you can dance to.

And after visiting a few websites of companies that sell these goods, I’m now getting ads telling me that for just over twelve Swiss Francs (about $14.09 U.S.) I could buy a wallet that holds 120 CDs and looks like a pair of blue jeans.

I still have CD shelves in my apartment! Where else would I put the CDs?

Moving cross country and trying to decide whether or not to keep the thousands of CDs… wallet or not. Seems so hard to believe I’ll use them enough to justify the schlep but also .. everything you wrote here. Dear Abby (Gabe), what should I do?