Notes for an Essay About Quitting Your Job and Leaving the Country

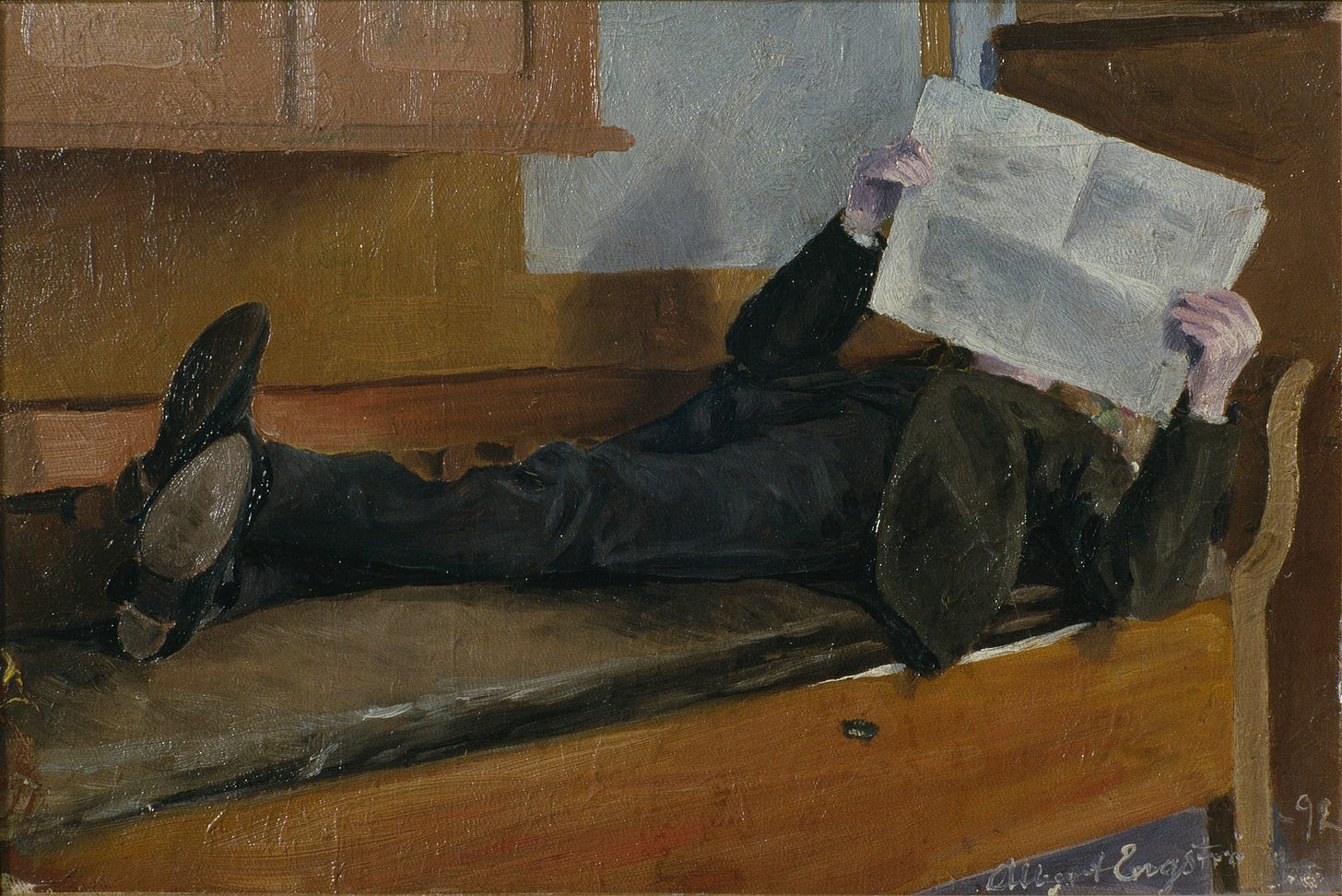

Draw a doodle of a bridge on fire

1. How to say goodbye

First put off saying anything. They’ll figure it out. The updated bio on social media, the “looking for work” tag on LinkedIn, the sudden amount of free time to send texts in the middle of the day—these are all hints to be taken by anyone who would care to hear the news.

That is a passive goodbye. Decide on it, then ask…Is it passive or passive-aggressive? Does it put a distance between you and others? Does understatement put reality at a distance? Question the tendency of your generation to make major life events seem small, like posting “we did a thing” as a caption on a photo of a wedding, a first child, or a newly purchased home.

Do we avoid outright bragging because bragging is, as we say, a bad look, or because we fear that the reaction might not be what we want? What if the announcement of a birth gets a more muted response than a picture of a particularly well-made pizza? Ask these questions until you convince yourself that online life compresses everything into units that are all the same size and weight. Despair. Decide that these questions do you no good and plan something else.

Plan a grand announcement. Think through the wording at your desk. Get up several times for water and, on the fifth or sixth excursion, leaf through that Joan Didion collection and reread Goodbye to All That. Consider outright parody. Decide on allusion. Something for the true heads. Prepare a comment on curtains then fret over whether it’s too pretentious. Go outside until pretentious impulses subside.1

Consider making a splash. Open a new document. Give it the name “The Real Dirt.” Imagine removing the filter and letting opinions and ideas to spill out of your mind. Draw a doodle of a bridge on fire. Pause. Realize there is no wave of scandal and instead only a trickle of gripes that apply to all institutions and almost all workers in the knowledge economy (ha) as they reach their late thirties. Study these gripes. Realize they are so generic that the document should be titled “Meditations on Middle Management in American Capitalism” or something adequately high-minded that will convince the reader even the boring parts (that is, most of the parts2) are profound.

Decide to put off saying anything.

2. The facts

Linda and I are moving to Switzerland, the country where she was born and where her parents live. Technically she has already moved and I’m in Washington deciding which of our possessions to give away and which to load into a shipping container and send to Basel.

Everything we own is laid out for assessment. There’s nowhere in our apartment where I can hide from the fact that we’re leaving. In every corner, there’s a stack of something ready for the movers to box up or for someone from the local Buy Nothing group to take way.

Work feels the same. For a variety of reasons, I can’t continue working my full-time job on the senior editorial staff of a midday public radio show while living in another country. Everyone involved agrees on this and there are no hard feelings. Now that we’ve announced I’m leaving, I’m the caretaker of a job, rather than the holder of it. I should put a disclaimer on my name in Zoom meetings: This is Gabe, he won’t be here much longer.

3. The data

I have worked in journalism for sixteen years. That’s forty-two percent of my life. Counting four years of college, I’ve spent fifty-two percent of my life either working in journalism or preparing to work in journalism.

We have lived in Washington, in the same apartment, for eight years. That’s the longest I’ve lived in any single place except my parents’ house. It’s twenty-one percent of my life.

These percentages are of my life so far. I don’t know how much they’ll figure into the total.

4. There’s a chance everything falls into the ocean

The movers sent us an insurance form to fill out. We need to list everything we own and how much it would cost to replace each item. It’s an autobiography written in purchases for an audience of actuaries. Our lives will be in the box, at least on paper. If everything falls into the ocean, we get a check.

5. The buried lede

In the middle of filling out the insurance form, I made another list. Because I’ve worked in journalism for so long, most of my friends are journalists. I wrote down the names of the ones I’m closest to. This was my first step toward networking. I could reach out and see if anyone needed an editor or a writer or someone to cut audio. Looking at the list, I realized that nearly every person had, at some point, been laid off from a job in journalism.

This is something I haven’t experienced. I’m lucky. This is the first time I’ve left a job without another one waiting. Once I left a job because a layoff was imminent, but every other time, it’s been a matter of what professionals like to call personal growth—a chance to try something new, take on a challenge, reach more people, make more money, learn. I like to learn.

In truth, I’m afraid. The real luck of having never been laid off is that I’ve never been without a steady paycheck in my adult life. I’ve also seen freelance rates drop and publications vanish. I’m worried I won’t be able to make a go of it.

We’re in a low moment now. Friends used to say they could only sell pieces if they dressed them up as clickbait or hot takes. Now there’s barely a market even for those. The big-dollar podcast deals have fallen through. News has always been about publishing pieces that are relevant, but the definition of relevant has narrowed for many publishers. In some cases, it means people are talking about this on Twitter or TikTok. Other times, it means that a larger outlet (almost always the New York Times) has published reporting, and now everyone needs a response. Breaking a new story takes time and effort. Time and effort take money. Criticism has lost most of its monetary and cultural value—reduced to a number on Rotten Tomatoes or pieces written for free by people who care3. Features are largely restricted to clean narratives, particularly narratives about crime. Online life compresses everything into units that are all the same size and weight.

Making all this worse is the fact that, for the last eight years or so, I’ve heard a persistent voice asking the question every journalist dreads: what if it doesn’t matter? In the early years of my career, stories had consequences. Strong reporting could move legislation and push out corruption. This didn’t happen a lot, but it was often enough to keep us going. Then it seemed to happen less and less, at least on the national level. We heard every kind of explanation for this; we are post-truth, post-shame, post-accountability. “The news cycle moves too fast” we say as we shovel more reaction stories into the engine.

6. The math

Going freelance means itemizing and putting a price on the work I do. Working for a salary means putting a price on work, too, but in an office job, it’s easy to confuse a salary with being paid simply to be yourself. Whether you’re chatting with work friends or slammed with back-to-back deadlines, your pay is tied to existence. I’m afraid going freelance will mean learning that the price for my work is near zero.

And if my accounting leads to this conclusion, then what? I will inevitably apply the value of my work to my value as a person. This is another result of being employed full-time. The life and the job become the same thing.

7. Yes, we are moving the record collection

Everyone asks. Now you know. Only the turntable isn’t going. It won’t spin at the right speed in a different country.

8. Meditations on middle management

The lack of available money for journalism has led to a conservatism in what gets published. The surest bets are preferred. Familiarity and certainty have value.

Can I complain about this? Haven’t I been on the inside figuring out ways to do more with less? Haven’t I sat underneath a gigantic screen showing website statistics in real time while I review pitches sent to me by freelancers? Haven’t I been pressed for time and decided that I just can’t do what it takes to make an interesting idea popular?

Can I say that publishers have lost their courage when I know full well it’s not courage that’s lacking, but energy, money, and audience?

9. The real dirt

I never planned to be in management. I didn’t imagine moving up the ladder when I thought about my career. I figured I would be a reporter forever and go from story to story, job to job, landing wherever I landed. My dreams were about the stories I would report, not the titles I would hold.

At first, having to manage people was a tradeoff for getting to set an editorial agenda and establish an office culture. Eventually, managing became its own reward. At a training seminar for people working in radio, an instructor said we should ask ourselves at the end of every day “what did I do to make the station sound better today?” The answer didn’t have to be big, she said. Most days it wouldn’t be. The important thing was to have an answer.

After that, I could spend all day trying to solve one issue for one person and go home feeling as satisfied as I did on those days as a reporter when I finally cracked a story.

As institutions grew larger around me and as the money and energy for reporting grew more scarce, the question came around again. What if it doesn’t matter? The role of a middle manager is, much of the time, to repeat things. Repeat a request for something from someone down the organizational chart, then repeat a response from someone high on the chart. Sometimes this becomes the entire job. Sometimes it just feels that way.

Faced with this, I wonder if I left reporting too soon. I was just hitting my stride when I changed course, and I’ve had some success freelancing on top of my day jobs. Why did I leave, I ask. As soon as the path up the ladder became available, I saw how my career would advance. I never saw that as a reporter. When I became a manager, did I choose money and security over risk? The life and the job are inseparable.

10. Lufthansa: STL - FRA - BSL

This move has been in the works for months. We’ve told our families. We’ve told our friends. We’ve told our landlords and our neighbors and the staff of our favorite local restaurant. Our apartment has been nothing but boxes for weeks. The move didn’t feel real until last Wednesday. That day, I bought a one-way ticket out of the country then announced in a work meeting that I was leaving.

11. Maybe this is the Didion part

One day in mid-June, I left my apartment to conduct an interview for a freelance story I’d sold. Smoke from wildfires in Canada clogged the air. Fliers on lampposts urged the president to call a climate emergency. A gray cloud hung in the high curves of the subway tunnels. I remembered a ride from a few months earlier. The station was full of photos of a man who had been struck by a stray bullet while at work. Below the photos were details to donate to pay for his funeral. That day, Linda and I were taking the train to the airport to fly to Switzerland and begin arrangements for our move. On the plane, I put in headphones and turned on music. David Bowie’s “Five Years” played. “News guy wept and told us, Earth was really dying.” It seemed like a coincidence.

The freelance story I was reporting was not timely. It was a feature but it wasn’t about crime. It didn’t have a gripping narrative. It had no villain and featured no one who had been done wrong. It was the story of a largely forgotten moment in popular culture history that explains a small, overlooked facet of daily life today. It was the type of story I love to pitch, even though these pitches are almost always rejected due to lack of timeliness or suspense. I had fortunately found an outlet that shared my interest.

After I finished my interview, I walked outside and put on one of the masks I had bought in bulk to wear inside during the pandemic. I had a headache. When I got home, I swallowed an aspirin, put an icepack on my head, and laid on the sunflower yellow couch in our living room. In the dark and under ice, I felt panic, like I had made a mistake. The ashes of a burning world filled the sky and I went out to report on something else. Shouldn’t every story be about the doom that’s facing us? I ask whether stories can make a difference, but shouldn’t I still try and only focus on the most pressing existential issue? Is asking whether a story matters nihilism or narcissism? Am I moving or am I escaping? Maybe I’m retreating. This is Gabe, he won’t be here much longer.

I took a drink of cool water and wondered whether the yellow couch should come with us to Switzerland.

12. I thought it would be easier to give away all our plants

We can’t take them with us. I don’t know if they would grow in a different climate. It’s also not allowed. They might grow too well.

13. This part is too sincere and needs distance

It’s been easy to turn my life into my job because I’ve always loved being a journalist. If not for interviews, I could go months without talking to someone I don’t already know. I love the way we can take the minutiae of our profession way too seriously in even the most dire circumstances, debating commas or going back and forth over just how much of a pause to keep in a clip of tape when the story in question is about the end of the world. I even love that needless misspelling of “lede” to mean to the opening of a story.

14. We did a thing

My headache and the smoke cleared over the weekend and I started writing my freelance assignment. I stared at a blank document trying to find an opening that would scream relevance. I looked for time pegs, anniversaries, updates. Then I gave up and just started telling the story.

There isn’t a narrative, but there so rarely is in life. Things happen. They don’t always happen for a reason. What matters is that they happened at all. A container might fall into the ocean, or the ocean might rise and take it. At least we’ll have a record of what was inside.

Note: They may appear to subside when, in fact, they have taken over, resulting in plans for a multipart meta-narrative that most readers will abandon by the second paragraph. This is good. Something for the true heads.

Note: Use self-deprecation sparingly, loser.

Hello.

Wow, wow, wow. Congrats on the move! Also, I relate to so much in this piece. It’s a knockout. Glad you are still writing here; writers like you are very much needed even if the world doesn’t understand that. Looking forward to reading dispatches from Europe.

The right thing will call to you. Don’t be afraid to listen.